Valuing Personal Goodwill in the State of Florida: Alternatives to Tangible Net Book Value

Introduction

The question of how to objectively value personal goodwill in a marital dissolution proceeding is one frequently encountered by business appraisers and attorneys in the State of Florida. Personal goodwill is defined as the portion of a business’ value in excess of tangible net book value that depends upon the personal reputation and continued presence of the marital litigant. Personal goodwill contrasts sharply with enterprise goodwill, which reflects the portion of a business’ value in excess of tangible net book value that relates to the reputation and competitive advantage of the business. Unlike enterprise goodwill, personal goodwill is not considered a marital asset subject to equitable distribution in the State of Florida. Consequently, personal goodwill must be excluded from the valuation of a closely-held company.

Several cases in Florida have made the valuation of a company difficult in the context of divorce, by linking the concept of personal goodwill to a non-competition agreement (see, for example, Schmidt v. Schmidt, Held v. Held, and Walton v. Walton). These cases reason that any goodwill value that depends upon the assumption of a covenant not-to-compete, must include an element of personal goodwill. Because of these cases, many business valuation experts have started to rely upon the tangible net asset value method, as a primary indicator of value in the context of divorce. This has led many closely-held companies to be undervalued.

The purpose of this article is to briefly review the case law history in the State of Florida relating to personal goodwill and to describe the consequences of utilizing the tangible net asset value method as the primary indicator of value. This article will also provide several alternative methodologies for valuing a closely held company that may result in a higher and more credible valuation than the adjusted net tangible asset value methodology. This article summarizes some additional factors that should be considered in developing a claim for enterprise goodwill in a marital dissolution action.

Overview of Florida Case Law

The seminal case dealing with the issue of personal goodwill in the State of Florida is Thompson v. Thompson. In this case, which dealt with a small law firm, the Florida Supreme Court ruled that for goodwill to be a marital asset it must exist separate and apart from the “reputation or continued presence of the marital litigant.”[i] The Court reasoned that if “goodwill depends on the continued presence of a particular individual, such goodwill, by definition, is not a marketable asset distinct from the individual.”[ii] Such value, although relevant in determining alimony, should not form the basis for equitable distribution. Thompson mandated “fair market value” as the exclusive method for valuing personal goodwill in the State of Florida.[iii]

Subsequent cases in the State of Florida further cemented the decision in Thompson. In the case of Young v. Young, for example, the 2nd District Court of Appeals stated that goodwill was not a marital asset if it did not exist “separate and distinct from the presence and reputation of the individual.”[iv] Similarly, in Christians v. Christians, the court concluded that goodwill is not divisible when it does not exist “separate and apart from the reputation and continued presence of”[v] the owner. These cases have primarily dealt with small professional services firms, such as accounting practices and doctor’s offices.

Several additional cases in the State of Florida have taken the issue of personal goodwill further, analogizing the concept to a covenant not-to-compete. In Walton v. Walton, the 2nd District Court of Appeals found that the most telling evidence of a lack of any institutional goodwill was the wife’s expert’s testimony that “no one would buy the practice without a non-compete clause.”[vi] The Court reasoned that “if the business only has value over and above its assets if the husband refrains from competing within the area that he has traditionally worked, it is clear that the value is attributable to the personal reputation of the husband.”[vii] Similarly, in Williams v. Williams, the Court concluded that the most “…telling evidence of the lack of goodwill…” is that “…no one would buy [the business] without a non-compete….”[viii]

In Held v. Held, the 4th District Court of Appeals also concluded that goodwill was personal in nature because no one would buy the business without a covenant not-to-compete and further analogized the covenant not-to-compete to a non-solicitation agreement, reasoning that “both limit a putative seller’s ability to do business with existing clients of the business.”[ix] Similarly, in Schmidt v. Schmidt, the Court remanded the trial court’s opinion reasoning that “…because the…[expert’s] value requires execution of a non-compete agreement, it is clear that such valuation still includes a personal goodwill component.”[x]

Standard Practice in Florida: Adjusted Tangible Net Assets

Because of the decisions in Walton, Williams, Held and Schmidt, the fair market value of a business for marital dissolution purposes in the State of Florida is often valued without the assumption of a commercially valid covenant not-to-compete. This assumption creates a unique set of challenges for appraisers and attorneys because many real-world business transactions often include covenants not-to-compete for a wide range of legitimate business purposes. Consequently, methods such as the income and market approach, which may often rest on these assumptions, are frequently ignored in the valuation of a small closely-held business in the State of Florida.

To deal with the “no-covenant” assumption, many appraisers and attorneys in the State of Florida have developed the practice of valuing a business for divorce purposes using the adjusted net tangible asset value method as the primary indicator of value. Under this method, only the tangible assets (i.e. cash, accounts receivable, property, plant and equipment) are adjusted to fair market value. No consideration is given to the future earnings capacity of the company or the intangible assets of the business. The underlying logic is that in the absence of a commercially valid covenant not-to-compete, the business would not sell for a meaningful premium in excess of hard assets (i.e. cash, receivables, equipment). After all, what rational buyer would pay anything above hard assets when the seller could immediately compete against the buyer?

The problem with this analysis is that many businesses with extremely valuable operations and enterprise goodwill are being appraised without any consideration for the value of those assets. The most extreme example of this reality occurred in the case of Kearney v. Kearney, wherein a multi-hundred million-dollar IBM distribution business with over 600 employees was valued at net liquidation value because the Husband proclaimed that his business “simply could not be sold in the marketplace without a non-compete…”[xi] Two years later the company sold for $109.5 million. Even the appellate court, which did not reverse or remand the opinion, found it “astonishing that [the Company]…[had] not a thimbleful of ‘institutional goodwill to its name.”[xii]

Alternative Methodologies for Excluding Personal Goodwill

With the rise of divorce cases involving possible claims of personal goodwill, it’s important for business valuators and attorneys to understand the alternative methods that are available to deal with the “no-covenant” assumption. Failure to consider these alternative methods could leave a substantial amount of money on the table in the context of the scheme of equitable distribution. The following provides a brief overview of the primary alternative methodologies that can be utilized to value a company without a non-compete.

1. Bottom-Up (Purchase Price Allocation) Method

One alternative methodology for valuing a business in the absence of a non-compete clause is the bottom-up (purchase price allocation) method. Under this method, the tangible and identifiable intangible assets are valued and adjusted onto the balance sheet. This method is very similar to the adjusted tangible net asset value method, except that, in addition to tangible assets, all readily identifiable intangible assets are also included on the adjusted balance sheet.

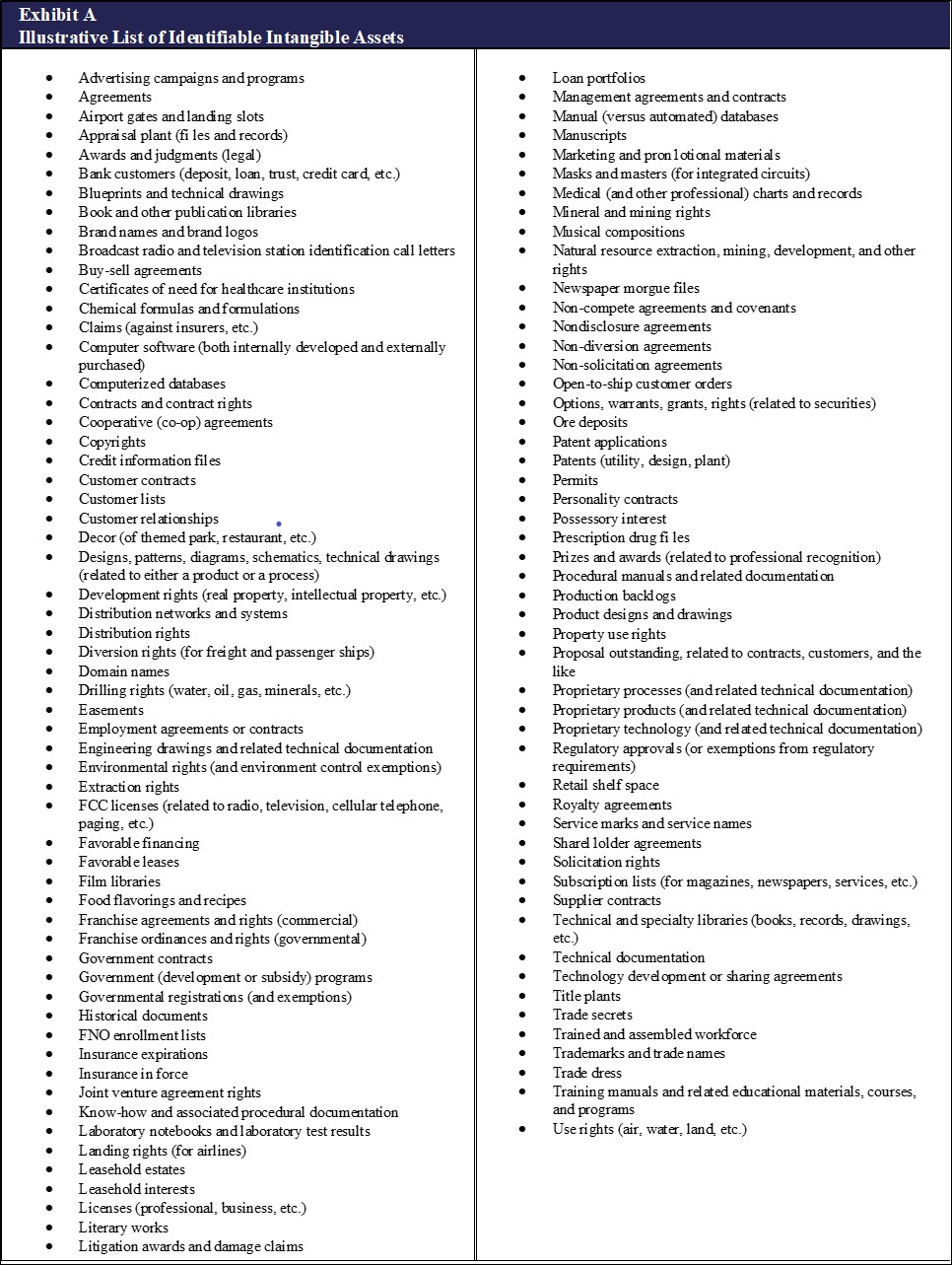

Identifiable intangible assets consist of a wide-range of valuable assets including, but not limited to, contracts in place, backlog of orders, favorable leases or leasehold interests, copyrights, patents, trademarks, licenses, distribution agreements, domain names, customer relationship assets, franchise rights, assembled workforces, computer software, databases, and trade secrets. A detailed list of common identifiable intangible assets that can exist in a business valuation setting is found in Exhibit A[xiii].

Ideally, each of the identifiable intangible assets in a business should be identified, valued, and included on the adjusted balance sheet. Often, many business valuators and attorneys overlook these valuable assets because they are not reported on the tax return or financial statements. For example, an assembled workforce, which can be a very valuable intangible asset of the business, is typically never listed as an asset on the balance sheet because the costs of training, recruiting, and hiring such personnel are expensed on the income statement. The value of the trained staff, however, is really no different that the value of the equipment, and the cost to replace such staff should ultimately be included as an adjustment. Collectively, making adjustments for all other identifiable intangible assets could represent a material upward adjustment to the reported net book value.

The advantage of the bottom-up (purchase price allocation) method is that all tangible and identifiable intangible assets, separate from goodwill, are recorded on the balance sheet. This method provides a more comprehensive and accurate reflection of the total net assets of a closely-held company, separate and apart from goodwill. The methodology, by definition, does not include the value of a covenant not-to-compete because such value is explicitly excluded from the determination of the adjusted balance sheet (i.e. no value is assigned to the covenant not-to-compete). In addition, this method is generally accepted within the profession, as it is commonly used to perform a purchase price allocation for financial reporting and tax purposes.

One disadvantage of this method is that each of the identifiable intangible assets must be valued, which can be a costly endeavor. In addition, although the methodology is generally accepted in the business valuation profession, it has not, as of the date of this publication, been reviewed by or subjected to any scrutiny of a family law court in the State of Florida. Furthermore, the methodology does not include an allocation for any enterprise goodwill as it only includes an adjustment for the identifiable intangible assets of the business separate and apart from goodwill. Consequently, if enterprise goodwill exists (i.e. value in excess of the tangible and identifiable intangible assets), such value would technically not be included in the value derived from this method.

Nevertheless, by individually appraising each of the identifiable intangible assets, a significant increase in value relative to the adjusted tangible net asset value method can be realized.

2. With-and-Without Method

A second methodology that can be utilized to value a business without a covenant not-to-compete is the with-and-without method. Under this method, the appraiser determines the fair market value of the business under two scenarios: (i) a scenario wherein the propertied spouse is assumed to remain in the business and (ii) a scenario wherein the propertied spouse is assumed to leave the company and compete with the business. The difference in value of the two scenarios is an estimate of the propertied spouse’s personal goodwill.

In performing this analysis, the appraiser needs to quantify the estimated loss in business revenue and cash flow caused by the propertied spouse’s assumed competition, including estimates of the changes in costs, timing and extent of revenue loss, and likelihood of competitive success.

This typically requires a detailed analysis and understanding of the sources of revenues and the amount of business that will be lost in the event of competition. An appraiser will typically gather detailed sales information by year, referral source, product line, service type, sales person/employee, geography, customer type, department, and the like, for a sufficient number of historical periods. With this information, a detailed study of the historical composition and sources of revenue is performed, with the objective of determining the sources which are highly dependent upon the continued presence of the individual and/or have a material risk of loss in the event of competition.

Revenue sources that are highly dependent upon the continued presence of the propertied spouse or have a high-risk of loss in the event of competition are assumed to be retained by the propertied spouse. The financial statements of the business are recast to reflect lower revenues and profits, and the business is valued with those lower revenues and profits. This removes any indication of value associated with the seller’s continued presence in the business.

Determining the loss in revenue attributable to the propertied spouse may seem like a speculative exercise. However, with detailed financial statements and adequate financial statement analysis, a supportable basis for opinion can often be meaningfully derived. Some of the types of analyses that should be performed to support the assumptions in a with-and-without analysis include:

- 1. An analysis of historical revenue by referral source to determine the portion of total revenue that is directly produced by the propertied spouse. Such information is often available in the company’s computer database or customer relationship management software, and can be utilized to illustrate the portion of revenue, if any, that is directly generated by the propertied spouse.

- 2. An analysis of revenue by product or service line to determine whether any product or service line is protected by law or contractual rights. Often, a business will have revenue that is protected by an exclusive contract or intellectual property rights, such as patents or copyrights. Such revenue would not be at high risk of loss in the event of competition.

- 3. An analysis of revenue by geographical market to determine whether sales are made to persons outside of the surrounding geographical area. A large portion of revenue to persons residing outside of the geographical market may indicate that the level of close personal interaction necessary to support a personal goodwill claim is small.

- 4. An analysis of revenue by sales person or employee to determine the portion of revenue services by different personnel in the organization. Often, such an analysis will illustrate certain individuals, other than the propertied spouse, are responsible for revenue sources of the business. Employees who have large revenue responsibility and are subject to pre-existing employment agreements or covenants not-to-compete may protect those revenue channels from loss.

- 5. An analysis of revenues by revenue channel to determine its sources. For example, a business may receive a substantial portion of revenue through website sales. The web domain is a transferable asset and business that is derived through that channel may not be attributable to personal goodwill.

In addition to analyzing the financial records, deposition testimony can provide additional supporting information for the primary channels of revenue that are at high risk of loss. Deposition testimony of key personnel, including sales staff, the owner, and potentially even customers or referral sources, may provide further empirical support for the portion of revenue that would be lost in the event of seller competition.

Once the portion of revenue that may be lost from competition is established, such revenue should be removed from the financial statements, including a reduction in the associated variable costs. Probability factors may also be considered if the likelihood of competition by the seller is less than 100 percent. This could be the case in a situation wherein the seller has significant barriers for re-entry into the marketplace, such as lack of access to available space to setup a new business. Often, an illustrative matrix of scenarios can be shown to demonstrate the value of the business assuming different scenarios for the loss in revenue or probability of competition.

The advantage of the with-and-without method is that the specific profits attributable to the propertied spouse are directly removed from the valuation. In addition, it specifically considers the valuation impact by removing the covenant assumption and, therefore, is not subject to the criticism of depending upon a covenant not-to-compete.

The primary disadvantage of this methodology is that the loss of revenue and profit in the competition scenario have to be supported based upon financial analysis. Without detailed financial information, such an analysis may be labeled as judgmental.

3. Discount for Lack of Covenant Method

A final method for valuing a business without a covenant is the discount for lack of covenant method. Under this method, the fair market value of the subject business is determined assuming the execution of a covenant not-to-compete. An analysis is then performed of the value allocated to a covenant not-to-compete in similar transactions. The value allocated to the non-compete clause is then subtracted from the conclusion of value as a “discount for lack of covenant.”

In this methodology, the appraiser will commonly rely upon a private market transaction database such as Pratt’s Stats. A search is conducted of recent sales transactions wherein a value was allocated to the covenant not-to-compete. The covenant’s value from each transaction is then expressed as a percentage of total intangible value to derive a covenant-to-intangible value ratio. The ratio is then multiplied to the fair market value of the intangible asset as an indicator of the value that would be assigned to the covenant not-to-compete. The resulting value is then subtracted from the business to derive the value excluding the value of the covenant.

For example, suppose an appraiser is calculating the fair market value of a physician’s practice. A database search of similar physician’s practices yields a median covenant-to-intangible ratio of 50%. Accordingly, assuming the firm was similar to the average company in the sample, 50% of the goodwill value would be allocated to the covenant not-to-compete/personal goodwill and removed from the valuation. A comparative table is often used to summarize the allocation range for all transactions.

The primary advantage of the discount for lack of covenant is that it relies upon actual values allocated to covenants not-to-compete in similar transactions. Accordingly, it can provide a market derived estimate of the value assigned to a covenant not-to-compete in similar transactions.

The main disadvantage is that the value assigned to the covenant not-to-compete may have been motivated by tax or other non-market reasons. In addition, only limited information is available for private transactions. It is also difficult to find a sufficient number of transactions to support a meaningful analysis.

Other Factors to Consider

In addition to the methodologies described above, it is also useful to perform a qualitative assessment of the factors that could contribute to the total goodwill. In the Supreme Court case of Thompson vs Thompson, the Court stated that the determination of personal goodwill is a “fact intensive” process that requires the assistance of expert testimony[xiv].

Therefore, developing a detailed factor list summarizing the primary drivers of total goodwill can be an extremely effective tool for identifying the factors contributing to goodwill value. The mere existence of an enterprise related factor could indicate that some of the goodwill value should be included as a marital asset in the scheme of equitable distribution.

The following provides a summary of the primary factors that could support the existence of enterprise goodwill:

- 1. Large businesses, which has formalized its organizational structures and institutionalized its systems and controls

- 2. Owner-employee has signed a pre-existing covenant not-to-compete with company

- 3. Owner-employee has employment agreement with company

- 4. The business is not heavily dependent on personal services

- 5. The business has significant capital investments in either tangible or identifiable intangible assets

- 6. The company has more than one owner, some of whom are not employees

- 7. Company sales result from name recognition, sales force, sales contracts and other company-owned intangibles

- 8. Company has supplier contracts and formalized production methods, patents, copyrights, business systems, etc.

- 9. Business has a favorable location

- 10. Business has established systems and organization

- 11. Business has significant repeating revenue stream

- 12. Business owns intellectual property assets.

- 13. Marketing and branding in name of business

- 14. The company’s employees are subject to employment agreements or covenants-not-to-compete

Of the factors listed above, a particularly interesting scenario occurs when the owner has signed a pre-existing covenant not-to-compete with the company (Item #2). In such a scenario, the individual could be deemed to have transferred his or her personal goodwill to the company, thereby converting their personal goodwill into a corporate asset subject to equitable distribution. Such a view has been supported in several IRS cases and T.C. Memos (see, for example, Howard v. United States, Martin Ice Cream v. Commissioner and Norwalk v. Commissioner), wherein the execution of a pre-existing covenant was deemed to have resulted in the “sale” of the individuals personal goodwill to the corporation.

The following factors support the existence of personal goodwill:

- 1. Ability, skills, and judgement of owner

- 2. Work habits of owner

- 3. Reputation of owner

- 4. Age and health of the professional

- 5. Comparative professional success of owner

- 6. Years of experience

- 7. Licenses, specialties, and awards

- 8. Interpersonal skills and personality

- 9. Closeness of contact

- 10. Important personal nature attributes

- 11. Marketing and branding in name of owner

- 12. Referrals to owner

- 13. Small entrepreneurial business highly dependent on employee owner’s personal skills and relationships

- 14. No covenant not-to-compete between company and employee-owner

- 15. No employment agreement between company and employee-owner

- 16. Personal service is an important selling feature in the company’s product or services

- 17. No significant capital investment in either tangible or identifiable intangible assets

- 18. Only employee-owners own the company

- 19. Sales largely depend on employee-owner’s personal relationships with customers

- 20. Product and/or services know-how and supplier relationships rest primarily with employee-owner

There are numerous other factors that could be considered in the context of a factor analysis. Once a detailed analysis of the factors is performed, such analysis could be tabulated, summarized, weighted, scored, and presented to the court. This can make an effective demonstrative exhibit at trial and can be very persuasive in terms of communicating the factors driving goodwill.

Conclusion

Florida case law relating to personal goodwill has made the valuation of a closely-held company within the context of divorce a difficult exercise. The difficulty largely stems from the fact that the courts view the existence of a covenant not-to-compete to indicate the existence of personal goodwill. Because of the precedent established by Florida case law, many appraisers and attorneys often value businesses in the context of a divorce using the adjusted tangible net asset value methodology, which may often leave a significant amount of money on the table.

Several alternatives to the adjusted tangible net asset value methodology, however, exist to value a closely-held company within the context of divorce litigation. These methodologies include: (i) the bottom-up (purchase price allocation) method, (ii) the with-and-without method, and (iii) the discount for lack of covenant method. These methods take a substantially more expansive view than the adjusted tangible net asset value method, and may result in a much larger equitable distribution claim than if net book value had been utilized.

In addition to these alternative methodologies, several factors contribute to personal goodwill, and these factors should be considered within the context of the divorce. Properly communicating the factors to the Court can assist in making a claim for enterprise goodwill, if any, in the business.

Collectively, utilizing the alternative methods and the factor based analysis can result in more equitable and credible outcome in the context of divorce. These tools can also be helpful for mediating a case and/or providing more reliable and competent evidence at trial.

Click here to download the PDF version of this article.

[i] Thompson v. Thompson., 576 So. 2d 267, (Fla 1991)

[ii] Thompson v. Thompson., 576 So. 2d 267, (Fla 1991)

[iii] Thompson v. Thompson., 576 So. 2d 267, (Fla 1991)

[iv] Young v. Young., 600 So. 2d 1140, 1992 Fla. App.

[v] Christians v. Christians., 732 So.2d 47 (1999)

[vi] Young v. Young., 600 So. 2d 1140, 1992 Fla. App.

[vii] Walton v. Walton., 657 So. 2d 1214, 1995 Fla. App.

[viii] Williams v. Williams., 667 So.2d 915 (Fla 1996)

[ix] Held v. Held., No. 4d04-1432 (Fla. 4th DCA 2005)

[x] Schmidt v. Schmidt., No. 4d11-3379 (Fla. 4th DCA 2013)

[xi] Kearney v. Kearney., No. 1D12–0754 (Fla. 1st DCA 2013)

[xii] Kearney v. Kearney., No. 1D12–0754 (Fla. 1st DCA 2013)

[xiii] Reilly, Robert F. and Robert P. Schweihs. 2014. “Intangible Asset Valuation Principles.” Guide to Intangible Asset Valuation. New York, NY: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, Inc.

[xiv]Thompson v. Thompson., 576 So. 2d 267, (Fla 1991)

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/teegardin/5537894072